A quick word first

Thanks for visiting The Jazz of Negotiation! When you have a chance, check out the About page to see the aim of this publication and how it can help you become a more effective negotiator. Thanks! Mike

Results from last week’s honesty survey

In this article we’re continuing to explore moral issues in negotiation, in a series that began in April. For starters, a big thank you to readers who responded to the survey I put up last week about whether an owner of a vacation cabin is obliged to reveal problems with the property to a potential buyer! Here’s a link to that piece.

With this new case, people were much more reluctant to tell the truth than they were in the April scenario. In that first one, the question was whether, as a buyer, you would tell an elderly owner that they had underpriced their property. Look at the difference in the highlighted cells:

April Scenario: Buying the underpriced cabin:

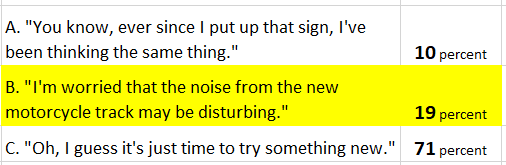

May Scenario: Prospective buyer asks why you’re selling such a beautiful place:

What’s going on here? The two scenarios deal with the same core issue: Whether you’re a buyer or a seller in a negotiation, must you disclose information when doing so could be costly? You might expect people to be consistent, yet they are twice as likely to be honest in the first case than in the second (40 percent versus 19). Understanding the causes of that flip can help us in our own decision making.

First, we may believe we have clear principles, but context matters. In the first scenario, the other party is a charming elderly person. It’s not stated whether they are male or female, but most people assume it’s a woman. Either way, reading the story might have reminded you of a much-loved grandparent. Maybe you relax and feel a certain empathy when you’re with older people. That may have prompted you to be more forthcoming.

In the second scenario you may have pictured a much younger couple, arriving in a fancy car. If you’re in the same age bracket, perhaps you felt something in common with them, but you also might have felt that they have responsibility to be well informed. As Murat put it answering the poll, “It’s my counterpart’s homework to check the municipality’s development plans.”

Others reacted differently. Ruby, favoring disclosure, spoke of Karma: “Sooner or later you will receive the same the same kind of treatment that you have bestowed upon others.” In the same spirit, others considered how they’d feel if someone misled them. It’s hard to justify setting a higher standard for others than you’re setting for yourself.1

Loss aversion may be another factor why people chose to be more truthful in the first scenario than in the second. Research shows that we feel the pain of losing $100 in cash more deeply than the pleasure of unexpectedly finding $100. In the second scenario, disclosing the new racetrack could feel like a loss, if it drives the price down. By contrast, informing the elderly owner that the cabin is underpriced may nevertheless lead to a deal that’s still below the buyer’s upper limit. So that’s a gain.

There may be a third factor, as well, namely how the issue arises. In the first scenario, the buyer who knows the cabin is underpriced has spent some time with the owner, maybe mulling whether to reveal that information. If he or she does so, the revelation is voluntary. In the second case, where the seller is asked about the motivation to move, that comes out of the blue and may trigger a defensive reaction.

Ralph Waldo Emerson said, “Foolish consistency is the hobgoblin of little minds.” Circumstances matter. What we’d do in one instance may not be how should act in another. But we should be mindful about what is prompting our choices.

Paltering?

One other thing struck me looking at the results of last week’s poll. Overall, four out of five people wanted to avoid revealing the damaging information. Of the two choices, the “it’s time to try something new” answer swamped the “thinking the same thing” option, by a whopping 71-to-10 margin.

In class discussion, I push those “try something new” people to explain why they prefer saying that to expressing second thoughts about selling (as the first answer implies). Most say that Option A is an outright lie, whereas their response (Option C) is not. To me that seems like hairsplitting. Yes, it is true that owner wants to move someplace else. But it’s not the whole truth by any means. It’s misleading, seemingly deliberately so, in that it omits the fact that their decision is triggered by upcoming noise in the area.

The fancy term for telling a half-truth is “paltering.” Again, we should ask ourselves how we’d react if someone else was being crafty with us.

There are two lessons here, one for each side of the transaction. For would-be buyers, it’s about asking questions the right way. Precision and persistence are essential. Asking general questions in negotiation invites vague answers. Be persistent pinning down details. If asked, “Are there any potential problems with the property that could give me a concern?” the seller might feel compelled to reveal more information.

Sellers, in turn, should think about how far they can go using this ploy. Even if they can conceal the actual truth, they may lose their credibility as buyers tire of the evasions.2 FN See my February piece on detecting lies; some of the content also relates to paltering.

Emotion and moral judgments

It would be nice if when we confront a choice that has moral implications, the first thing we’d consider is our values: who we aspire to be and how we want others to see us. Unfortunately, there’s compelling research indicating that’s not how it works. Instead, many of our moral judgments are visceral. NYU professor Jonathan Haidt puts it succinctly: “Moral reasoning, when it occurs, is usually a post hoc process in which we search for evidence to support our initial intuitive reaction.”3

That’s an unsettling claim. It challenges the notion that we are principled actors who reach moral conclusions through reflective inquiry. But that’s not what neuroscientists have discovered when they conduct fMRI scans of subjects being asked to make choices.

When people are presented with ethical quandaries, the emotional parts of the brain that register fear and disgust, or empathy and desire, fire up before the conscious mind kicks in. Those first reactions color our subsequent thinking. We’re good at concocting justifications for what are actually gut responses. If someone pokes a hole in our rationale, we can come up with another argument without realizing what’s actually driving our thinking.

Some emotional responses are sound and praiseworthy, of course. The fleeting thought of cheating somebody may trigger self-contempt or disgust. That’s good. So is the compassion we feel for someone who deserves a decent slice of the pie. But our first impressions require a second look.

As you ponder hard choices, remember Mark Twain’s advice: “Do the right thing. It will gratify some people and astonish the rest.”

Housekeeping

Just by signing up for Jazz of Negotiation, you’ll get free access to a full article, plus a shorter post, delivered by email 50 weeks a year. Paid subscribers get additional content: Q and A threads, videos, and from time to time, short exercises, with more to come.

Other responders offered some interesting observations. Tony suggested that he’d take the property off the market and try to block the motorcycle track. Sunanda noted that some buyers might not regard the motorcycles as nuisance. (That made me think that bikers might be willing to pay a premium!)

See my March article, The Sad Truth about Lie Detection, for tips on spotting lies (and maybe paltering, too).

See Haidt’s classic text, The Righteous Mind.